|

Case Report

Serum negative immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy mimicking hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case report and review

1 Medical Student, College of Medicine, University College Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Road, P.O. Box 200212, Ibadan, Nigeria

2 Department of Medicine, University of Chicago Medicine, 5844 S. Maryland Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA

Address correspondence to:

Chinedu Nwaduru

College of Medicine, University College Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Road, P.O. Box 200212, Ibadan,

Nigeria

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100087Z04CN2020

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Nwaduru C, Couri T, Pillai A. Serum negative immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy mimicking hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case report and review. Int J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis 2020;10: 100087Z04CN2020.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy (IAC) is a systemic manifestation of IgG4-related diseases manifesting with an increased serum level of IgG4. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy often has a robust clinical response to steroid therapy, however making a diagnosis can be difficult as the cholangiographic features may resemble that of cholangiocarcinoma with varying immunological profiles. In the absence of features suggestive of malignancy, a high index of suspicion for the disease should be maintained, even in the presence of normal serum levels of IgG4.

Case Report: In this case report, the diagnosis of IAC was made following cholangiographic imaging, along with the presence of retroperitoneal fibrosis and thickened urothelia, although serum IgG4 levels were within normal limits. The resolution of biliary strictures following a trial of steroid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis.

Conclusion: Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy requires a combination of clinical, serological, histopathological, and radiological features in order to make a clear diagnosis. A trial of steroid therapy in the event of an unclear clinical presentation further helps in differentiating IAC from hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Cholangiocarcinoma, Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy, Steroids

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy (IAC) is one of the systemic manifestations of IgG4-related diseases manifesting with an increased serum level of IgG4 and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates rich in IgG4 cells [1]. Establishing a diagnosis can be difficult as the cholangiographic features of IAC may resemble that of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), pancreatic cancer, or cholangiocarcinoma, with variable biochemical and immunological patterns [1]. Even in the absence of any other suggestive features of malignancy, a high index of suspicion for IAC should be maintained in the presence of normal serum levels of IgG4 and a hilar mass on cholangiography [1],[2]. In this case report, we observed a rare presentation of IAC, manifesting with normal levels of IgG4 levels. The resolution of strictures following two weeks of steroid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of IAC, clearing differentiating it from cholangiocarcinoma (an often inoperable cancer of the biliary system). A unique aspect of this case was the presence of bilateral thickened urothelia with hydronephrosis, which was suspicious for malignancy. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy can present with a hilar mass and normal serum levels of IgG4, which can be misdiagnosed as hilar cholangiocarcinoma, resulting in unnecessary surgical intervention. Thus, a combination of clinical, serological, histopathological, and radiological evaluation is required prior to any operative procedure.

Case Report

A 47-year-old Caucasian male with a past medical history of hypothyroidism and gastroesophageal reflux disease presented with a three day history of painless scleral icterus, decreased appetite and energy, pruritus, acholic stools, and dark urine. He had no personal or family history of liver disease and denied alcohol or intravenous drug use. His physical exam was notable for scleral icterus, jaundice, and a normal abdominal exam. Liver chemistry tests demonstrated cholestasis and transaminitis, with total bilirubin 6.3 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 192 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 547 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 160 U/L. Total protein, albumin, complete blood count, and basic metabolic panel were all normal.

The following day the patient was admitted for an expedited workup. Laboratory findings revealed an elevated CA 19-9 level of 199 U/mL, normal IgG level of 1089 mg/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) 0.9, lipase 48 U/L, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) 2.3 ng/mL, des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin 0.6 mg/mL, acetaminophen assay <1.0 mcg/mL, negative anti-nuclearb antibody and anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) 2.4 mIU/mL.

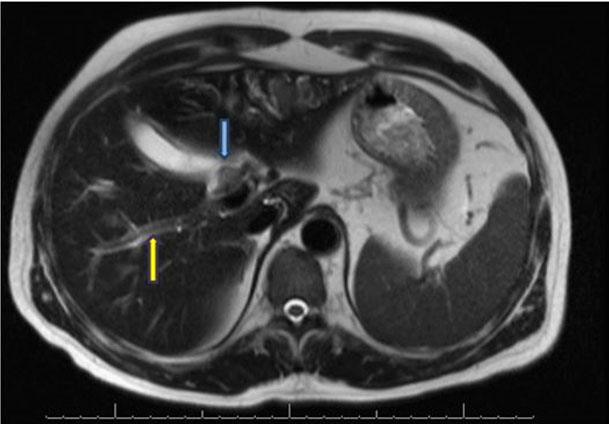

An abdominal ultrasound showed intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation without common bile duct (CBD) dilation, plus diffusely increased hepatic echogenicity suggesting steatosis/hepatocellular disease. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed severe intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with caliber change at the common hepatic duct (CHD) at the bifurcation (Figure 1). In addition, there was an associated mass-like area of T2 hypointensity within the anterior left hepatic lobe with prominent intrahepatic vessels and retroperitoneal fibrosis. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed normal upper endoscopy and a 25 mm by 13 mm hilar mass with upstream intrahepatic ductal dilation. Bilateral plastic stents were placed and brushings and biopsies were taken of the hilar mass, which showed reactive ductal epithelium without dysplasia or malignancy.

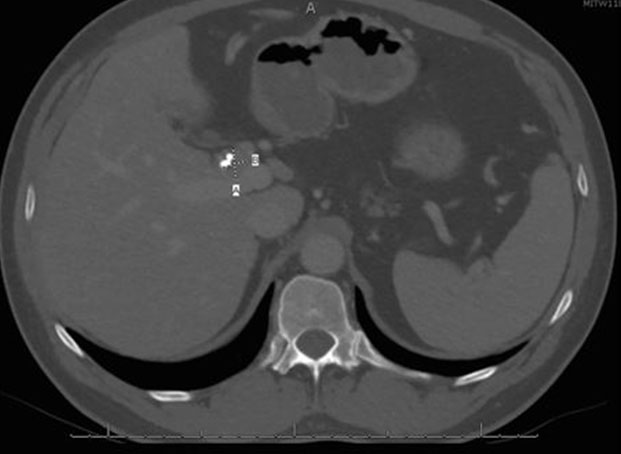

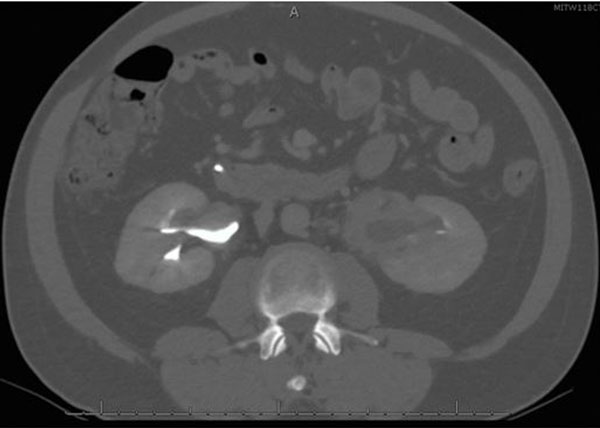

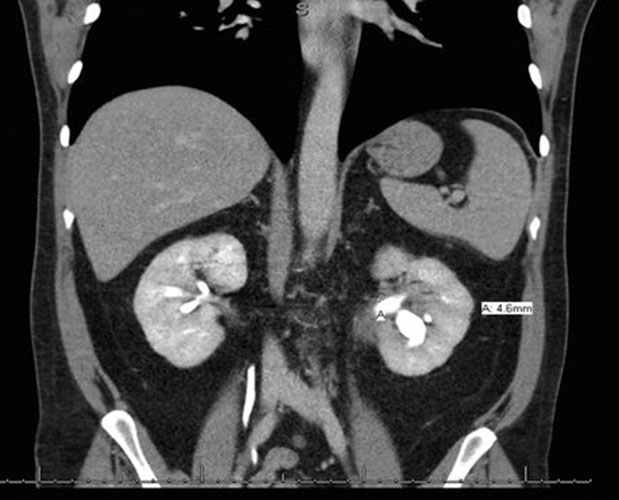

He was discharged from the hospital and seen in surgery clinic, where a bile duct resection, left liver lobe resection, and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for possible cholangiocarcinoma were recommended. At this point, he reported that his initial symptoms had improved since his ERCP. His physical exam was normal and his liver chemistry tests revealed mild transaminitis. Total protein and albumin were normal. A computed tomography (CT) abdomen with contrast demonstrated a mass-like thickening of the CHD wall near the right and left hepatic duct bifurcation measuring 13 mm by 17 mm (Figure 2). He also had bilateral hydronephrosis, worse on the right, with abnormal mass-like thickening of the urothelia and retroperitoneal fibrosis on the CT (Figure 3). Given this finding, the differential diagnosis included consideration of IgG4 cholangiopathy, however measured IgG4 was normal at 42.4 mg/dL. A week later, he underwent another ERCP for continued imaging abnormalities and to reobtain tissue to rule out malignancy, which showed mild but improved structuring from the CHD to the hilum and redemonstrated the hilar mass. Samples of the mass for cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were taken, and the stents were replaced.

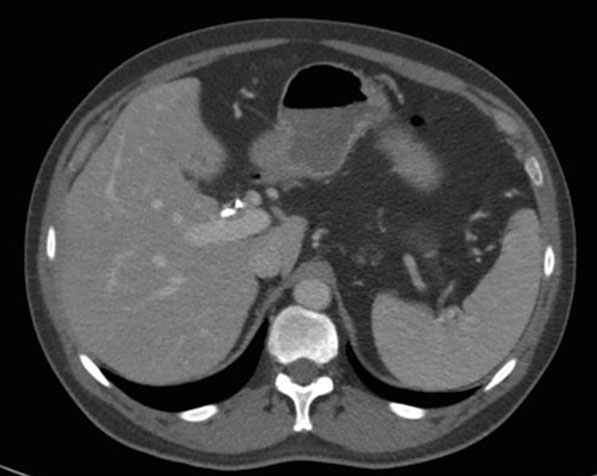

Two days later, he was referred to hepatology clinic for further workup. A trial of empiric prednisone, dosed at 40 mg twice per day, was started on account of concerns for IAC. The pathology results showed reactive epithelia only, without malignancy, and negative for FISH, IgG, and IgG4 stains. He returned to hepatology clinic three weeks later reporting resolution of all of his previous symptoms since initiation of prednisone. All his liver chemistry had improved to normal. The repeat CT scan showed improvement in the mass-like thickening of the CHD, now measuring 9 mm by 4 mm (Figure 4), with improvement in the urothelial thickening and resolution of the hydronephrosis. His prednisone was decreased to 40 mg once a day and thereafter to 30 mg once per day (Figure 5). Three weeks later he continued to be asymptomatic, and a repeat CT scan showed improvement in the mass size, continued CHD wall thickening, and resolution of his biliary ductal dilatation. A repeat EUS and ERCP done three weeks after the scan demonstrated resolution of the hilar mass and marked improvement of the CHD structuring, and the stents were removed. Brushings from the hilum were negative for malignancy. A month later, the patient started complaining of weight gain, muscle aches, and insomnia. The prednisone dose was then tapered to 20 mg per day and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 500 mg twice per day was added to his regimen. He continued to remain asymptomatic, liver chemistry tests remained normal, and repeat CT scans showed overall improvement in his CHD wall thickening (Figure 6). He continued to feel well on this regimen and denied any complain.

Discussion

Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy (IAC) is viewed as a biliary manifestation of a systemic group of diseases: IgG4-related systemic disease (ISD) [1]. Defined as a syndrome characterized by elevated levels of serum IgG4 and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates rich in IgG4 cells, ISD is a constellation of various manifestations, depending on the organ involved [2]. A review by Bjornsson in 2007 reported that IAC has been given many names, including “lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis” [3], “sclerosing pancreatocholangitis” [4],[5], “pancreatic pseudotumor with multifocal idiopathic fibrosclerosis” [6], “inflammatory pseudotumor from sclerosing cholangitis” [7], “atypical primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with unusual pancreatitis” [8], “immunoglobulin G4-related lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholangitis,” “autoimmune pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis” [9], and “lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholangitis without pancreatitis” [10]. Interestingly, all of these names seen throughout the literature suggest a strong overlap between various immunopathologies of the biliary tree and adjacent structures.

Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy is a subtype of sclerosing cholangitis, alongside PSC and secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC), and has been recognized internationally as a clinical entity in the spectrum of IgG4-related diseases [11]. However, there have been reported cases of IAC misdiagnosed as cholangiocarcinoma due to cholangiographic similarities, leading to major surgical resections such as hepatectomy or hepaticojejunostomy and radical bile duct resections [12],[13],[14],[15].

Seen as a biliary manifestation of a systemic autoimmune disorder with typically characteristic IgG4-positive histopathology lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, IAC commonly includes intrapancreatic and extrapancreatic biliary strictures [13]. Other organ involvement seen in patients with IAC includes salivary glands (sclerosing sialadenitis), retroperitoneal fibrosis, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy [16],[17],[18]. In a study by Ghazale et al., 49 out of 53 (92%) patients with IAC had pancreatic involvement, making the pancreas the most common organ involved in IAC [2],[11]. However, there have been several reports of patients with IAC in the absence of pancreatic involvement, with some cases masquerading as hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Paradoxically, compared to the majority of autoimmune conditions, there is a male preponderance of IAC, with a male to female ratio of 3.3:1 [2],[9],[19]. In a case series report from Japan by Nakazawa et al. between 2004 and 2005, males accounted for over 70% of patients. Although frequently seen among elderly males, with about 83% of patients older than 50 years at diagnosis [2], IAC can manifest among patients younger than 50, with an age range of 14–85 years in early studies of the disease [2],[4],[9]. More recent studies have shown a more revised age range of 47.6–87.4 years with an average age of 69.3 [19].

Clinical features of IAC on presentation are variable, but obstructive jaundice is a common manifestation, seen in over 77% of cases including this index report [2],[3],[4][9]. Other features include steatorrhea (15%), weight loss (51%), abdominal pain (26%), and new-onset diabetes mellitus (8%) [2].

A mimicker of IAC is cholangiocarcinoma, which can present as a hilar mass. Serum tumor markers are often used to further assess for cholangiocarcinoma. However, several reports in literature have shown that high levels of the tumor marker CA 19-9 are quite common in patients with IAC [3],[9],[20],[21],[22]. The CA 19-9 level of this report was elevated over five times the normal value. In a study by Rosen et al., one of the criteria to establish a clinical diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma included the presence of a malignant appearing biliary stricture and CA 19-9 >100 U/mL, both of which were present in the patient [23]. However, the sensitivity of elevated CA 19-9 for cholangiocarcinoma is only 40–70%, with a specificity range of 50–80%, and a positive predictive value of 16–40% [13],[24],[25]. In addition, elevated CA 19-9 levels cannot be used definitively to diagnose cholangiocarcinoma.

There have been reported cases of renal manifestations of IAC, mimicking the features of a urothelial carcinoma. In their case report, Zhang and his colleagues described a case of IgG4-related kidney disease manifesting as thickened urothelium with prominent fibrosis and numerous lymphoid follicles on histological examination of the renal pelvis [26]. Many of these renal manifestations showed a left to right kidney predominance, which was observed in our patient [27],[28]. Although the cytological studies came back normal, the resolution of the urothelial thickening in response to steroids is in keeping with IAC, ruling out the possibility of a malignancy.

Eosinophilic cholangiopathy, a benign cause of biliary obstruction may mimic hilar cholangiopathy and affect the extrahepatic biliary tree with similar clinical manifestations as IAC [29]. However, eosinophilic cholangiopathy is characterized by dense transmural eosinophilic infiltration of the biliary tract independent of peripheral increase in eosinophil count [29], a feature that was absent in our patient.

More than 80% of patients with IAC have significantly increased levels of liver chemistry tests, including alkaline phosphatase and serum bilirubin [9],[30]. The level of gamma-globulin in patients with IAC are often elevated, especially the IgG4 levels, which are increased in 60–80% of cases [5],[12],[31],[32],[33]. Although the serum IgG4 levels in our patient were normal, patients with IAC have been reported to present with variable biochemical and immunological abnormalities at the time of diagnosis, including with normal serum levels of IgG4, a rare manifestation [9],[21]. Studies have shown that only 18% of IAC cases reveal IgG4 plasma cells through transpapillary endoscopic biopsy, with a sensitivity of 54–86% [15],[34].

A study by Nakazawa et al. in 2005 showed sclerosing changes in the intra-and extrahepatic bile ducts in 50% of the patients during cholangiography, as was observed in this patient. Cholangiographic features are a useful tool in establishing a diagnosis of IAC in patients. Although pancreatic involvement is commonly seen in IAC, some reports have described isolated biliary tract involvement without features of pancreatic involvement, as observed in our patient [10],[35],[36].

In establishing a diagnosis of IAC, many patients are discovered to have IAC only after a major surgical resection, including hepaticojejunostomy and pancreatoduodenectomy [3],[5],[7],[9],[36]. The Japanese clinical diagnostic criteria of 2012 for IAC (HISTORt Criteria) remain a useful tool in the establishment of a clinical diagnosis for IAC, and our patient met the criteria as a definite diagnosis of IAC, with biliary tract imaging of segmental narrowing of the intrahepatic bile duct and thickening of the bile duct wall and the coexistence of retroperitoneal fibrosis [37]. In the case report by Bjornsson et al., they concluded that diagnosis of IAC is confirmed if biliary or other organ histology showed infiltrative IgG4 positive cells (>10 cells/hpf), or if the stricture responds with steroid treatment as seen in the patient. Yadav et al. also described normal serum IgG4 and IgG4 positive plasma cells <10/hpf in the sclerotic phase of IAC due to delayed presentation and dense fibrosis, as was observed in our patient [34].

In a retrospective study by Nishino et al., the use of steroids brought about the resolution of obstructive jaundice and biliary strictures in all patients, with the ducts improving to normal diameter in 60% of the patients [38]. In the treatment of IAC, it has been reported in the literature that the use of steroids for two to three months with an initial dose of 40 mg of prednisolone for four weeks, with tapering by 5 mg per week thereafter, proved useful in the resolution of symptoms [9]. Our patient had complete resolution of his liver chemistry tests and biliary ductal dilatation, and his structuring markedly improved, with prednisone. However, the presence of the CHD thickening and some stricturing, especially proximal extrahepatic or intrahepatic structuring, even after commencement of steroids in patients with IAC, is a prediction for relapse [2],[11]. Ghazale et al. reported that after steroid treatment with prednisolone, 29 patients (97%) responded to steroids with 18 patients (60%) showing resolution of strictures and stabilization of hepatic enzymes. Relapse occurred in 53% of these patients, of whom six were treated with immunomodulatory drugs. Two were placed on mycophenolate mofetil 750 mg twice daily with no further relapse. All six patients who were placed on immunomodulators for relapse were in remission with no further relapse (median follow-up on immunomodulators ranged from two to nineteen months) [2].

Conclusion

Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangiopathy is a distinct biliary disease entity with varying systemic organ manifestations. Although not frequently seen, IAC may be associated with renal manifestations, including urothelial thickening and hydronephrosis that can mimic other conditions. Cholangiographic features of IAC have a similar resemblance to the appearance of hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and thus distinguishing between these two diseases requires a high index of suspicion, especially in the absence of other features suggestive of a malignancy. Although serologic evidence did not suggest IAC in this report, improvement in laboratory, radiographic, and endoscopic abnormalities with steroid therapy confirmed the diagnosis of IAC, establishing the usefulness of steroid treatment in the diagnosis of IAC, a clear distinction between IAC and hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

REFERENCES

1.

Kamisawa T. IgG4-positive plasma cells specifically infiltrate various organs in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2004;29(2):167–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: Clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology 2008;134(3):706–15. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Kawaguchi K, Koike M, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Tabata I, Fujita N. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis: A variant of primary sclerosing cholangitis extensively involving pancreas. Hum Pathol 1991;22(4):387–95. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Erkelens GW, Vleggaar FP, Lesterhuis W, van Buuren HR, van der Werf SD. Sclerosing pancreato-cholangitis responsive to steroid therapy. Lancet 1999;354(9172):43–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, et al. Clinical differences between primary sclerosing cholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2005;30(1):20–5.

[Pubmed]

6.

Clark A, Zeman RK, Choyke PL, et al. Pancreatic pseudotumors associated with multifocal idiopathic fibrosclerosis. Gastrointest Radiol 1988;13(1):30–2. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Jafri SZ, Bree RL, Agha FP, Schwab RE. Inflammatory pseudotumor from sclerosing cholangitis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1983;7(5):902–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Yamada T, et al. Atypical primary sclerosing cholangitis cases associated with unusual pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48(39):625–30.

[Pubmed]

9.

Björnsson E, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Lindor K. Immunoglobulin G4 associated cholangitis: Description of an emerging clinical entity based on review of the literature. Hepatology 2007;45(6):1547– 54. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, et al. Cholangiography can discriminate sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis from primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60(6):937–44. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Nakazawa T, Naitoh I, Hayashi K, Miyabe K, Simizu S, Joh T. Diagnosis of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19(43):7661–70. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Mizutani S, Suzuki H, Yoshida H, Arima Y, Kitayama Y, Uchida E. Case of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis with a normal serum IgG4 level: Report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch 2012;79(5):367–72. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Zaydfudim VM, Wang AY, de Lange EE, et al. IgG4-associated cholangitis can mimic hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gut Liver 2015;9(4):556–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Erdogan D, Kloek JJ, ten Kate FJ, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing cholangitis in patients resected for presumed malignant bile duct strictures. Br J Surg 2008;95(6):727–34. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Miki A, Sakuma Y, Ohzawa H, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing cholangitis mimicking hilar cholangiocarcinoma diagnosed with following bile duct resection: Report of a case. Int Surg 2015;100(3):480–5. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Kamisawa T, Okamoto A. IgG4-related sclerosing disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14(25):3948– 55. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Ohara H, Nakazawa T, Sano H, et al. Systemic extrapancreatic lesions associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2005;31(3):232–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Hamano H, Arakura N, Muraki T, Ozaki Y, Kiyosawa K, Kawa S. Prevalence and distribution of extrapancreatic lesions complicating autoimmune pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 2006;41(12):1197–205. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

19.

Tanaka A, Tazuma S, Okazaki K, Tsubouchi H, Inui K, Takikawa H. Nationwide survey for primary sclerosing cholangitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2014;21(1):43–50. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

20.

Nieminen U, Koivisto T, Kahri A, Färkkilä M. Sjögren’s syndrome with chronic pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, and pulmonary infiltrations. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92(1):139–42.

[Pubmed]

21.

Hirano K, Shiratori Y, Komatsu Y, et al. Involvement of the biliary system in autoimmune pancreatitis: A follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1(6):453–64. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

22.

Fukui T, Okazaki K, Yoshizawa H, et al. A case of autoimmune pancreatitis associated with sclerosing cholangitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis and Sjögren’s syndrome. Pancreatology 2005;5(1):86–91. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

23.

Rosen CB, Heimbach JK, Gores GJ. Liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma. Transpl Int 2010;23(7):692–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

24.

Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin RD, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: An update. Gut 2012;61(12):1657–69. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

25.

Patel AH, Harnois DM, Klee GG, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95(1):204–7.

[Pubmed]

26.

Zhang H, Ren X, Zhang W, Yang D, Feng R. IgG4-related kidney disease from the renal pelvis that mimicked urothelial carcinoma: A case report. BMC Urol 2015;15:44. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

27.

Takata M, Miyoshi M, Kohno M, Ito M, Komatsu K, Tsukahara K. Two cases of IgG4-related systemic disease arising from urinary tract. [Article in Japanese]. Hinyokika Kiyo 2012;58(11):613–6.

[Pubmed]

28.

Inoue S, Takahashi C, Hikita K. A case of IgG4- related retroperitoneal fibrosis from the renal pelvis mimicking bilateral hydronephrosis. Urol Int 2016;97(1):118–22. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

29.

Saluja SS, Sharma R, Pal S, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Differentiation between benign and malignant hilar obstructions using laboratory and radiological investigations: A prospective study. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9(5):373–82. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

30.

Takikawa H, Takamori Y, Tanaka A, Kurihara H, Nakanuma Y. Analysis of 388 cases of primary sclerosing cholangitis in Japan; Presence of a subgroup without pancreatic involvement in older patients. Hepatol Res 2004;29(3):153–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

31.

Tabata T, Kamisawa T, Takuma K, et al. Serum IgG4 concentrations and IgG4-related sclerosing disease. Clin Chim Acta 2009;408(1–2):25–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

32.

Tabata T, Kamisawa T, Takuma K, et al. Serial changes of elevated serum IgG4 levels in IgG4-related systemic disease. Intern Med 2011;50(2):69–75. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

33.

Lytras D, Kalaitzakis E, Webster GJ, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma or IgG4-associated cholangitis: How feasible it is to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions? Ann Surg 2012;256(6):1059–67. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

34.

Yadav KS, Sali PA, Mansukhani VM, Shah R, Jagannath P. IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis masquerading as hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Indian J Gastroenterol 2016;35(4):315–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

35.

Hamano H, Kawa S, Uehara T, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing cholangitis that mimics infiltrating hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Part of a spectrum of autoimmune pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62(1):152–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

36.

Zen Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis with and without hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, and sclerosing pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis: Do they belong to a spectrum of sclerosing pancreatitis? Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28(9):1193–203. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

37.

Ohara H, Okazaki K, Tsubouchi H, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis 2012. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2012;19(5):536–42. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

38.

Nishino T, Toki F, Oyama H, et al. Biliary tract involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 2005;30(1):76–82.

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

We thank John Fung, MD, PhD (Department of Surgery, University of Chicago) for his contributions and comments to the manuscript.

Author ContributionsChinedu Nwaduru - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Thomas Couri - Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Anjana Pillai - Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2020 Chinedu Nwaduru et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.